Much it concerns a man, forsooth, how a few sticks are slanted over him or under him, and what colors are daubed upon his box.

인간이 실제로(forsmooth, 과연) 그의 위 아래에 몇개의 막대기(기둥)가 기울여 지는지(몇개의 기둥을 기울려 놓는지) 그의 상자(집)에 무슨 색을 칠할지 더 신경을 쓴다.

It would signify somewhat, if, in any earnest sense, he slanted them and daubed it;

좀더 적극적인 표현을 하자면(in any earnest sense) 그가 그것들(기둥을 them 으로 지칭)을 기울여(받혀) 놓고 거기에 칠한다(daub)면 다소나마(somewhat) 의미가 있을 것이다. (he는 건물주. 집주인이 제손으로 기둥을 대고 칠을 손수 할 수 있었다면 그나마 의미가 있을 것이다. would signify;과거완료. 실제론 그렇지 못함)

but the spirit having departed out of the tenant, it is of a piece with constructing his own coffin,—the architecture of the grave, and “carpenter,” is but another name for “coffin-maker.”

하지만, 정신이 제자리를 떠난 마당에, 그것(기둥을 대고 칠을 하는 것)은 묘지 건축물이라 할 수 있는 그 자신의 관을 건설하는 일부가 되었고 목수는 관 제작자의 또다른 이름이다.

One man says, in his despair or indifference to life, take up a handful of the earth at your feet, and paint your house that color.

누군가 인생에 대한 실망(despair)과 무관심(indifference) 끝에 발 밑에 흙 한줌을 퍼서(take up) 당신의 집에 흙칠을 하라고 한다.

* He(One man), You, I 는 각각 누구를 지칭하는지 유의하자

* 치장에 더 능란한 목수에게 별 생각 없이 집짓는 일을 주문하고 있는 당신에게 실망한 그는(현자? 저자?) 그냥 집은 결국 무덤일 뿐이니 흙칠이나 하라고 말하고 있다.

Is he thinking of his last and narrow house? Toss up a copper for it as well.

그의 마지막 좁은 집(무덤)을 생각하는 것일까? (그렇다면) 으례 하던대로 동전(copper)을 던지자(저승가는 노자돈, 그리스 전설에 있다고 함).

What an abundance of leisure he must have! Why do you take up a handful of dirt?

그는 참 한가한 모양이다! 왜 당신은 흙 한줌 집어들려 하는가? (왜 당신의 인생이 흙 한줌으로 취급되려고 하는가)

Better paint your house your own complexion; let it turn pale or blush for you.

당신의 집은 당신 자신의 안색으로 칠하는 편이 낳다. 색을 창백하거나 발그레(blush) 하게 바뀌게 하자.

An enterprise to improve the style of cottage architecture! When you have got my ornaments ready I will wear them.

어느 기업이 (당신의)오두막 건축 양식을 개선해 주겠는가! 당신이 내 장식물을 준비해 뒀다면 나는 그것을 걸칠 것이다(뭔 소린가?).

<47-1>

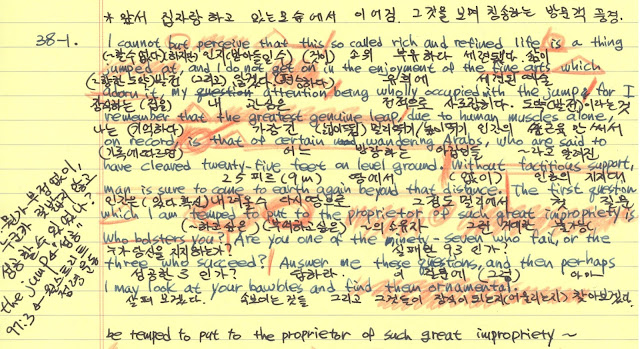

Before winter I built a chimney, and shingled the sides of my house, which were already impervious to rain, with imperfect and sappy shingles made of the first slice of the log, whose edges I was obliged to straighten with a plane.

겨울이 오기전에 굴뚝을 세웠고, 이미 빗물 방수(impervious)를 해놓은 벽면에 통나무를 처음 켜서(slice) 만든 고르지 못하고(imperfect, 불완전한) 생(sappy, 수액을 머금은, 생기발랄한)널판지, 대패(a plane)로 반듣하게 해야했던(be obliged to straighten) 테두리를 가진 널판지(shingle)로 널을 댓다(shingled).

* 이미 빗물이 스미지 않게 방수 처리해 놓은 벽면에 널판지(shingle)로 널을 댓다(shingled). 이 널판지는 생 통나무를 켜서 만들었는데 들쭉날쭉해서 그대로 쓰지 못하고 할 수 없이 패패로 모서리를 곧게 만들어야 했다.

결국 나는 단단한(tight) 덧댄(shingled) 회벽(plastered) 집을 가지게 됐다. 크기는 폭 10피트, 길이 15피트, 높이(posts) 8피트에 다락(garret)과 벽장이 있고, 양 벽면에 커다란 창이 나 있으며, 두개의 내림창(trapdoor)과 한면에는 문이 반대편에는 벽돌 벽난로가 있다.

The exact cost of my house, paying the usual price for such materials as I used, but not counting the work, all of which was done by myself, was as follows;

내 집의 정확한 비용은 다음과 같다. 내가 사용했던 재료들의 통상가격으로 지불한 비용이며, 내 힘으로 했던 일의 품삯은 제외된 것이다.

and I give the details because very few are able to tell exactly what their houses cost, and fewer still, if any, the separate cost of the various materials which compose them:—

그리고 자세히 적었는데, 자기집의 비용을 정확하게 말할 수 있는 사람은 거의 없고(very few) 있더라도(if any) 구성하는 다양한 자제의 세목 비용을 알고 있는 사람은 더욱 없기(fewer still) 때문이다.

Boards, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $8 03 ½, mostly shanty boards.

판자(대부분 판자집에서 뜯어온 것)

Refuse shingles for roof and sides, . . . . . . 4 00

지붕과 벽면 널판지

laths, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 25

욋가지

Two second-hand windows with glass, . . .2 43

중고 유리 창문

One thousand old rick, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 00

헌 벽동 1,000장

Two casks of lime, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 40 That was high.

석회 두통(비쌈)

Hair, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0 31 More than I needed.

섬유(필요이상 분량)

Mantle-tree iron, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0 15

Nails, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . 3 90

못

Hinges and screws, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0 14

경첨과 나사못

Latch, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0 10

쐐기

Chalk, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0 01

백묵

Transportation, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 40 I carried a good part on my back

수송비(대부분 등짐져 나름)

In all, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $28 12 ½

총합

These are all the materials excepting the timber stones and sand, which I claimed by squatter’s right. I have also a small wood-shed adjoining, made chiefly of the stuff which was left after building the house.

이것들이 무단점유자(squatter)의 권리에 따라 채취한 목재, 돌, 모래를 제외한 재료들의 전부다. 이외 집에 맞다은(adjoining) 나무헛간(wood-shed)을 집지은 후 남은 자재로 만들었다.

<47-2,3>